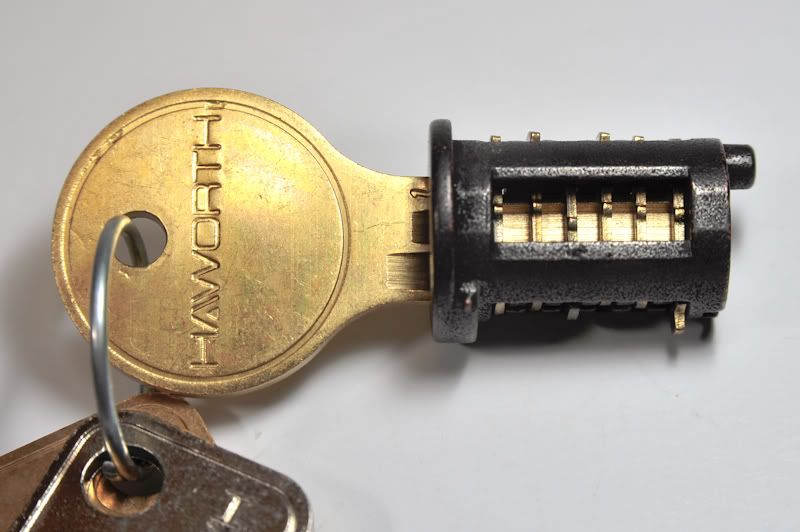

This camlock is made by Haworth, and can be found in a variety of office furniture, including desks, storage cabinets and filing cabinets. It's exactly what it looks like: a low-security wafer camlock. (The code stamped on its face is an indirect keycode that describes the cuts for the operating key -- in this case, for Haworth's ML-series of cores.)

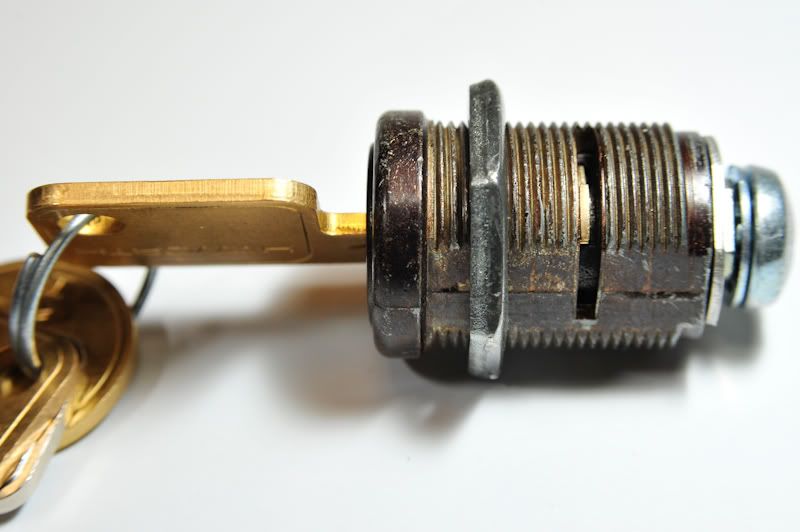

Unlike most simple wafer locks, however, these have the advantage that the cylinders are masterkeyed and, with the proper change key, the locks can be rekeyed quickly with interchangeable cores. The first outward indication that this isn't a standard cylinder is the groove that's milled through the outer lock body, through which you can see the last wafer:

The last wafer is trapped inside the groove. It rotates freely as the plug turns, but it has a very heavy spring that keeps it in position; this prevents the plug from being pulled out and removed from the lock body:

The reason this works is that the normal operating keys are too short to reach the last wafer. Regardless of how the operating key is cut, the last wafer will remain extended:

Haworth has one change key (CK-1) that works across all of their line of cores. (The change key will not unlock the lock, it will only allow you to remove the core from an unlocked lock.) As you would expect, the change keys are one space longer than the operating keys, which allows them to reach the last wafer:

The first five cuts on the change keys are not actually used; their only purpose is decorative, to make the change key look more complicated than it is. (The position of the first five wafers doesn't matter if you're removing the core: they only matter if you're trying to rotate the core.) The sixth cut on the change key depresses the sixth wafer (the core-retaining wafer), which retracts it out of the groove... this then frees the core, so that it can be slid out the front of the lock body:

If you look closely at the above photo, you'll see that the last wafer -- which was previously protruding above the plug -- now has a small tab protruding below the plug, once the change key has been inserted. This is a design feature, which (if the lock is installed properly) will prevent the change key from removing the core of a locked cylinder. The small tab protrudes into a cut-out extension at the rear of the lock body; you can see the narrowing of the channel and the cut-out section at 12-o'clock in the photo below:

That cut-out doesn't exist in the other channels, which means that the "core retaining" wafer can only be withdrawn by the change key when the cylinder is in the unlocked position. (This means that, in the locked position, the change key is blocked from entering all the way.)

The other feature of these locks is that they are masterkeyed. In an office environment, each employee would have a key that only opens their own desk -- but one master key could be given out to a department manager, for example, that opens all of the desks and cabinets in their department. Haworth produces their master keys on nickel-silver blanks, to help visually distinguish them:

The master keys look similar to the standard operating keys. They're only long enough reach the first five wafers, and the cuts on the master keys aren't related to the cuts on the brass "employee" keys:

The trick that these locks use is that the top of the keyway is quite wide, allowing for two different key blanks to fit into the lock. The blade of the "employee" keys is on the left, whereas the blade of the master keys is on the right; this means that the cuts on the "employee" keys lift the wafers from the left, and the cuts on the master keys lift the wafers from the right:

This has the added advantage that you can't cut down an "employee" key to make a master key.

The wafers themselves are cut differently on the left and the right, corresponding to where they would rest on either an "employee" or a master key. The first number stamped onto the wafer indicates the "employee" cut, and the second number indicates the master key cut:

In order to provide some degree of control over the master keys -- and to prevent situations where the head of the Advertising Department could open desks in the Legal Department, for example -- there are typically a number of master keys:

Each of the master keys typically have the same pattern of cuts, but they're each cut on different blanks with different warding, to prevent them from fitting into the locks belonging to any of the other departments:

The warding on the change key is thin enough that it can fit into any of the locks. (This obviously implies that you could make series of grand-master and grand-grand-master keys by controlling the warding on the blanks -- but I'm not aware of having seen any in practice.)

I know that there's likely not much new here for our resident locksmiths -- but hopefully this was of some interest to some folks.