Over the years there have been a number of different makes of "seal padlock" used for official sealing of government warehouses, boxcars and distilleries.

- Source: National Locksmith, Guide to Antique Padlocks

- "Seal padlocks were manufactured by the American Seal Lock Co., Pyes, Slaymaker, and others for governmental agencies as well as private companies, railroads, etc. The purpose of the seal is to detect tampering with the lock during shipment or transportation of the locked container."

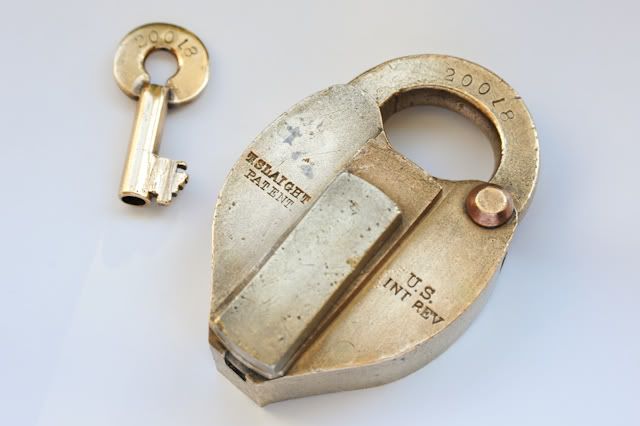

Thomas Slaight of Newark, New Jersey filed the patent on his new "paper seal" padlock on November 13, 1872 and received US Patent #141,519 on August 5, 1873. (There is a typo on the first page of the patent document, indicating "1878" for the issue date of the patent, which is incorrectly reported in a few different sources.)

These heavy-duty padlocks were manufactured from cast brass. The key is a simple, single-bit key and the keyway is similarly uncomplicated: there is a single post, with minimal warding, and no curtain protecting access to the 3 locking levers. The key turns counter-clockwise to throw the spring bolt and open the lock, and the warding is simple, with two notches (one on the bottom of the key, and one just above the top-most lever cut) helping to hold even heavily-worn keys in proper alignment with the lever pack. The keyway itself is covered by a spring-loaded cover, designed to help keep the padlock somewhat clear of rain, snow, dust and dirt.

The keys and shackles are stamped with matching serial numbers.

The locking design was well thought-out, with a dead-latching mechanism that prevented shimming of either the shackle or the seal cover:

- Source: National Locksmith, Guide to Antique Padlocks

- "Note that the tip of the shackle has a hole which the locking bolt enters, what we would now call 'deadbolting.'"

While the locks are strong and well-made, what made these locks revolutionary was that they introduced a cheap means of letting you verify that nobody else had opened your lock. This made them ideally suited for sealing places like warehouses and freight train boxcars -- places where thieves may be tempted to break in, and where small thefts might otherwise go unnoticed for a while.

- Source: United States Internal Revenue Stamps: Lock Seals (Walter W. Norton, 1912)

- "Lock seals are used at distilleries, warehouses and breweries by the internal revenue storekeeper or gauger, who is in charge of the plant. The places where distilled spirits are made, drawn or stored are under his supervision, and as a safeguard and precaution they are locked with a peculiarly constructed padlock so made that a paper seal or label can be inserted to cover the keyhole, making it impossible for any one to open the lock without punching a hole in the paper seal. Glass lock seals were used prior to the paper seals, but as they broke occasionally in the lock, causing trouble, they were discontinued and the paper seals took their place."

The "seal" on the lock was a piece of paper, inserted behind a special locking plate.

The plate securely held the paper in place, directly over the keyway; in order to open the lock (with either a key or with lockpicks) you first have to break the paper seal. Spikes in the plate hold the paper seal firmly in place, so it cannot be slid out of position.

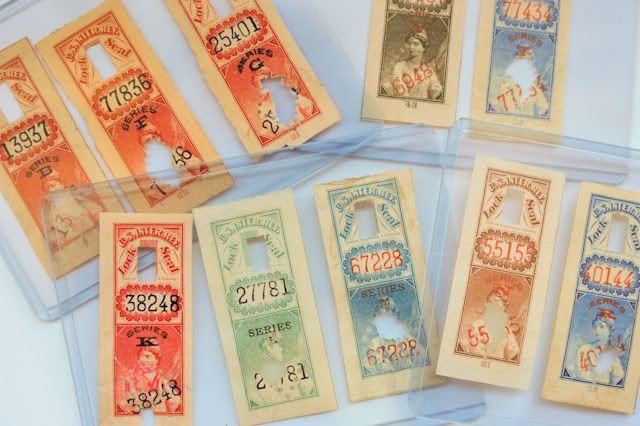

For extra tamper-resistance, the seals have the serial number repeated over the area that the key (or picking tools) would have to punch through in order to gain access to the keyway. Starting in 1888 the colours of the seals were also regularly rotated (initially every 30 days).

- Source: United States Internal Revenue Stamps: Lock Seals (Walter W. Norton, 1912)

- "The sheets of seals printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing are sent out from Washington to the Collectors of Internal Revenue and by them distributed to the different storekeeper gaugers in their respective districts. A record is kept by each collector of the number of sheets sent, serial letter, date, etc., and a report is made by the gauger, accounting for each seal received."

While the seals are sometimes referred to as "stamps", they were printed on non-adhesive paper, in sheets of fifty-four (six rows of nine seals per sheet). When cut, the individual seals are 18mm wide and 48mm high; from the selection of stamps I have (spanning from the early 1920's to the late 1940's), it appears that the sheets of seals were hand-cut as needed, rather than machine-cut.

The inside of the lock and key stem naturally pick up bits of the seals as they're punched in by the key. The layering of seal paper "sediment" inside the lock can provide a rough means of dating when the lock entered and left service, and whether it was kept on and used privately (e.g., by a distillery) after their use was no longer mandated by the government. The following picture shows the collection of paper seal shards that was removed while cleaning a single seal padlock and key:

While other designs of seals and seal padlocks existed at the time, the previous sealing devices were either simple lead seals (which could be opened and often resealed without detection), or padlocks whose keyways were covered with glass seals. The glass fragments in the glass seal padlocks were an example of technology that, while theoretically secure, had a number of problems in practice.

- Source: Boston and Providence Railroad Corporation (July 11, 1871)

- "The customs locks furnished by the Department are a very poor article indeed. We are constantly having trouble with them. […] We sometimes find that we can't lock them, but they get all right [sic] again after considerable shaking."

There was clearly an issue with glass shards working their way into the lever pack and jamming the locks.

The records of the 44th Congress show that a considerable number of complaints had been made over both the reliability and also the high cost of the government-mandated glass-seal locks. In 1872, an American glass-seal lock cost $5 for the lock, and $11.76 for a year's supply of glass seals. (In 2011 dollars, that's equivalent to approximately $310 to buy and operate one of those padlocks in its first year.) In contrast, Thomas Slaight was charging $3 per lock for his paper-seal padlocks at the time, and the paper seals were far cheaper to produce than the glass seals.

In response to the concerns of cost and reliability, the US Treasury Department established a committee to find a replacement for the sealing devices that were in use at the time to secure untaxed rail shipments and warehouses of alcohol. The committee quickly convened and issued a general tender, asking for manufacturers to send samples of their locks to Washington for the committee to review on March 31, 1873. This led to immediate and considerable objection from the many rail operators who had already made significant investment in the existing lock technology; one of many letters of objection was from Blue Line Railway:

- Source: Blue Line Railway (March 26, 1873)

- Sir: Our notice has been drawn to the above proposal, which indicates that you contemplate the use of another lock.

We cannot believe your attention has been fully called to the subject or that you are aware of assurances given us by Secretary Boutwell, that he should permit no further change, when we consented after a very lengthy controversy to the use of the American seal-lock.

Under a distinct understanding with your Department, we threw away all our old locks, and fully equipped our roads with the locks he prescribed, at a very heavy original outlay.

These locks we have had on our cars less than one year. Our employes as well as your officials are thoroughly acquainted with their use, and everything connected therewith perfectly systemized. The Canadian government has officially approved the system and adopted the glass seal for the protection of their customs department.

We spent months in harmonizing conflicting interests which must occur whenever a change is made in the manner of sealing, desiring thereby to meet your views. The locks and seals in every particular are giving entire satisfaction, as well as in protecting the Government. The Canadian government will still require us to use the glass seal, and should you prescribe another our cars must carry two locks, which would work a great inconvenience and hardship.

We also respectfully submit whether committees, having little or no experience in railroad business, are the parties to pass upon new inventions with a view to their adaptation to our railways.

Any lead or paper seal we consider worthless, affording insufficient protection to the Government and to our freight. The lead can be easily pried out and replaced or duplicated; the paper affected by the weather, as well as duplicated by photography and otherwise counterfeited, and not adapted to rough usage, especially in inclement weather; and under no circumstances can we consent to their use.

As a result of the lobbying from the owners of the existing locks, the committee postponed their search for six weeks, but -- after much controversy -- ultimately signed a contract with Thomas Slaight on October 24, 1873. Their criteria for selecting a suitable lock were:

- 1st, that it should not be easily picked;

- 2d, that if at any time it should be tampered with, it should itself make known the fact;

- 3d, that is should combine simplicity with security;

- 4th, that it should be as far as possible water-tight;

- 5th, that the works inside should be composed of a metal or metals not easily corroded by water;

- 6th, that as the locks are to be used and examined at all hours of the twenty-four, and by common workmen, oftentimes in haste, they should, as far as possible, be adapted to the capacities and exigencies of such men.

- Source: Letters, Reports, and Other Papers relative to Locks and Seals used in Internal Revenue and Customs Service of the Government, Submitted to the House Committee on Expenditures of Treasury Department for Investigation, 44th Congress, 1st Session (1876)

Thomas Slaight was already an established locksmith at the time; a brief description of his display appears reports from the first Industrial Exhibition in Newark in 1872:

- Source: Newark Industrial Exhibition: First exhibition of Newark (N.J.) Industries (1872)

- "In metal articles, such as mechanics' tools, coach hardware, horse and harness trimmings, etc.. the display is very fine. [...] Thomas Slaight, a case of padlocks, door locks and other fastenings."

The locks were produced for and used by various US government treasury branches between 1872 and 1953; the Bureau went through many reorganizations over those 81 years, with correspondingly different markings on the padlock bodies:

- Treasury Department [1872-1920]

- Bureau of Internal Revenue (Int Rev) [1920-1927]

- Bureau of Prohibition [1927-1930]

- Bureau of Industrial Alcohol (BIA) [1930-1940]

- Bureau of Internal Revenue (Int Rev) [1940-1951]

The Bureau went through more transitions than those five -- including a brief stint as the FBI's Alcohol Beverage Unit for several months in 1933 -- but I can only find records of padlocks produced for the four Treasury divisions listed above. While the Bureau of Engraving and Printing stopped printing the seals for the locks in 1951, the locks continued to be popular with distilleries, and remained in private use for years after. It should be noted that Government-issue locks from the 1930's and 40's, marked B.I.A., are often attributed as having been produced for the Bureau of Indian Affairs; so far as I can tell, that is incorrect, and those locks were actually used by the Bureau of Industrial Alcohol.

Slaymaker purchased Thomas Slaight's company in 1904, and the New Jersey registers record a Decree of Dissolution of the Thomas Slaight Lock and Manufacturing Co. on Dec. 20, 1904. After Slaymaker purchased the operations, manufacturing was moved to their plant in Lancaster, PA; the former site of the Slaymaker Lock Factory still exists in Lancaster, now converted to retail and cultural space.