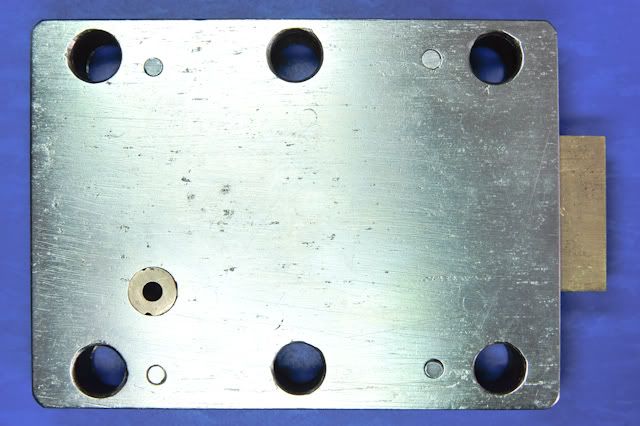

It's an 8-lever safe lock, with a number of interesting features.

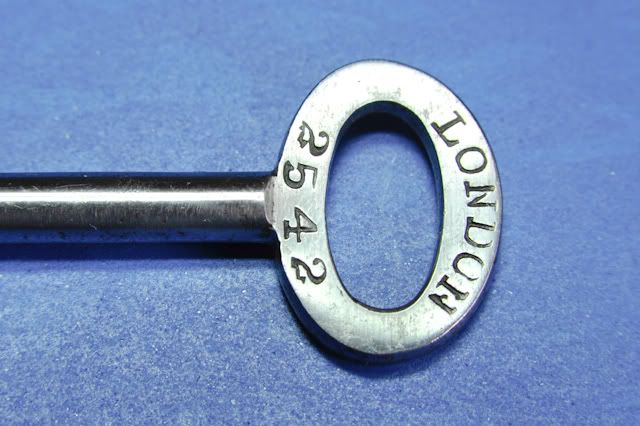

Daniel Ratcliff left Milner's and formed his own company, under the name Ratcliff & Horner, in 1890. Looking at the serial numbers of the locks that have a known production date, this one (serial #2542) appears to have been produced in 1893. The company changed names, and was reincorporated as Ratner Safe Company a few years later, in 1895.

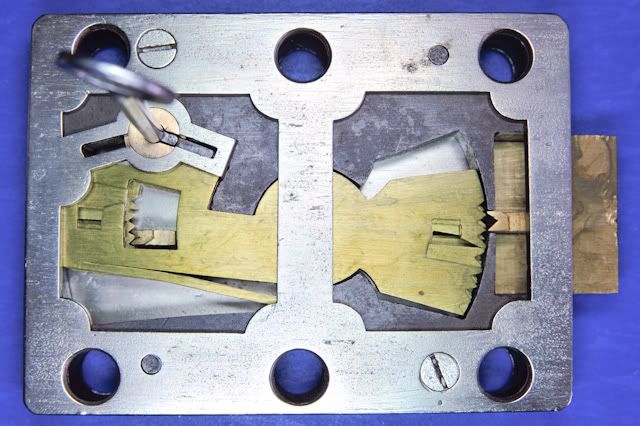

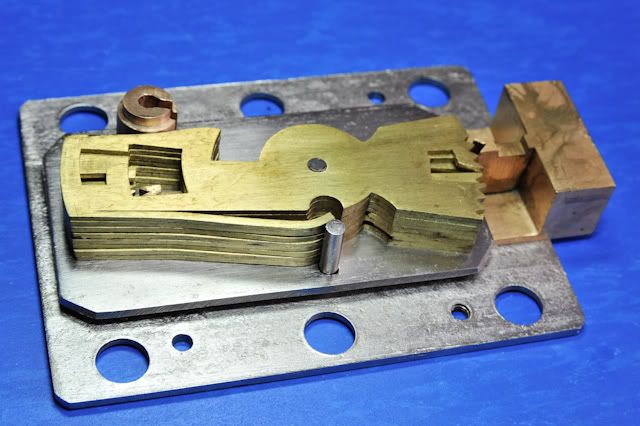

Similar to many designs of the period, the bolt has two stumps that interact with each lever, in order to complicate the feedback and make picking much harder:

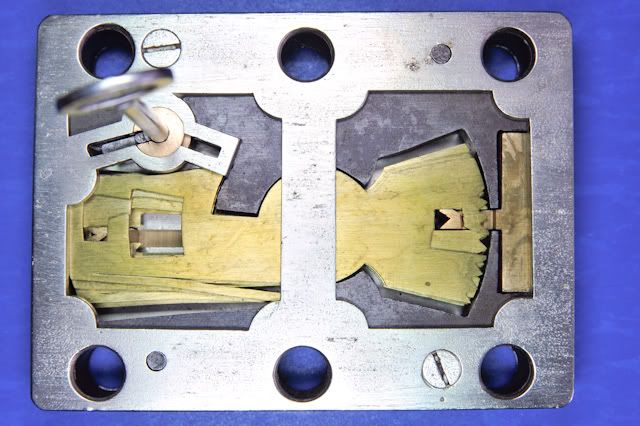

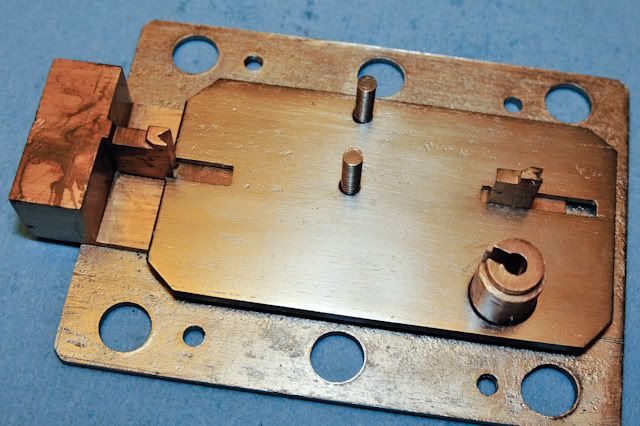

Also, like many locks from the period, one of its main features is a substantial IDB (Iron Door Block). While today's lock manufacturers are concerned with outdoing one another with "Anti-Bumping" claims, safe manufacturers in the late 1800's were trying to outdo one another by conducting public demonstrations and blowing open each other's safes with gunpowder. The solution to this was to cast a large iron block that fills up as much of the space inside the lock as possible -- leaving as little "open" space in the lock as possible.

Daniel Ratcliff had a controversial involvement with these public safe-breaking demonstrations. He was overseeing one infamous public demonstration of safe-breaking, on April 30, 1860 in Burnley (acting on behalf of Milner's), when his men packed too much gunpowder into one of George Price's safes; the resulting explosion blew the door clean off the safe, injuring a large number of bystanders and killing a young child.

Notable in this same model is that -- unlike later production models -- there are no channels cut into the IDB to vent explosive gases (from gunpowder attacks) away from the lever pack and bolt stumps.

With the IDB removed, you can get a better view of the interactions between the lever pack and the bolt stumps:

An interesting feature of this lock, intended to complicate the feedback while picking, is that a number of the levers are half-levers -- interacting with only one of the two stumps.

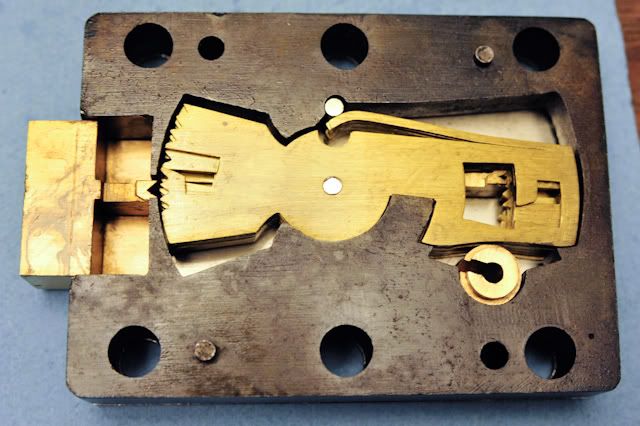

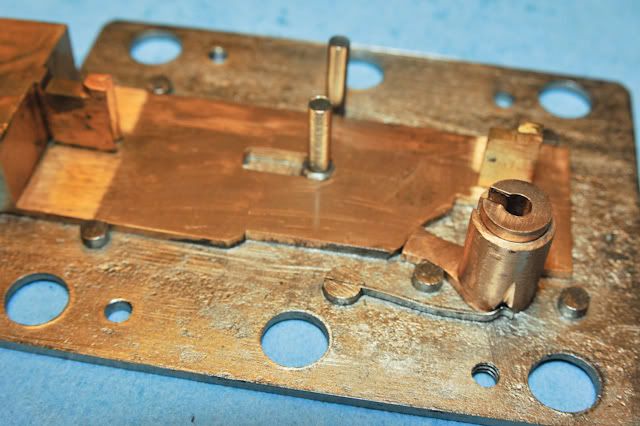

The curtain also throws the bolt, which is hidden under a steel plate:

This design has a number of benefits. From a security standpoint, it ensures that the bolt can only be tensioned by rotating the curtain (which makes picking harder), and the steel plate further restricts access from the keyway into the rest of the lock body (useful when your competitors were trying to fill your locks with gunpowder). As a side-benefit, it also spreads the force of throwing the bolt across the entire key -- which makes them less susceptible to breakage.

Overall, a neat piece of history, and quite well preserved.